Motor lamination stacking is a critical process in electric motor and generator manufacturing, directly influencing efficiency, magnetic performance, mechanical strength, and production cost.

Whether your application focuses on high-efficiency electric vehicle motors or rugged industrial drives, choosing the right stacking method can make or break performance targets.

A Quick Comparison Table

| Stacking Method | Core Focus | Best For |

| In-Mold Glue Dispensing | Adhesive bonding | High precision & low loss cores |

| Out-Mold Glue Dispensing | Flexible glue application | Small-medium batch production |

| Progressive Mold Self-Interlocking | Mechanical locking | High-volume, high-throughput |

| Compound Mold Single Punch Self-Interlocking | Combined stacking and shaping | Extremely high volume lines |

| Rivet Stacking | Mechanical fastener | Simple, rugged motors |

| Welding Stacking | Metallurgical bonding | High-stress, high-speed motors |

| Self-Adhesive Stacking | Pre-coated adhesive layers | Compact & medium motors |

| Bolt Stacking | Reversible clamping | Prototyping & testing |

| Buckle/Clamping Stacking | External mechanical pressure | Temporary assembly & labs |

| Al-casting/Cu-casting Stacking | Metal encapsulation | Rotors & integrated cast cores |

In-mold Glue Dispensing

In-mold glue dispensing applies adhesive directly inside the stacking mold during assembly. As motor laminations enter the mold, controlled pressure ensures uniform bonding, resulting in precise stack geometry suitable for high-efficiency, low-loss motor cores.

In-mold glue dispensing is often found in high-end motor lines. Uniform glue application and controlled compression help minimize flux discontinuities and noise.

| Pros | Cons |

| Excellent stack alignment | Higher mold and equipment cost |

| Reduced core loss | Requires precise adhesive control |

| Better mechanical stability | Longer setup and maintenance |

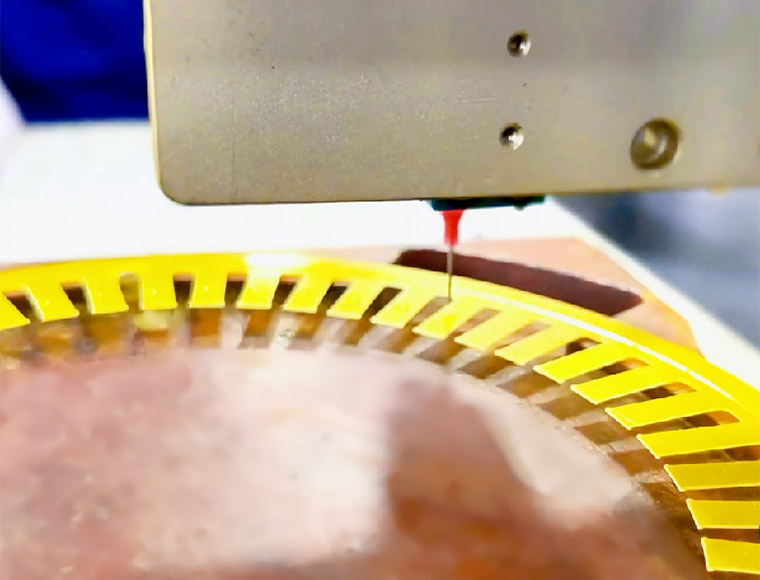

Out-mold Glue Dispensing

Out-mold glue dispensing applies adhesive to laminations outside the mold before stacking and pressing. This method provides flexibility in glue type and volume but places greater emphasis on operator skill and handling procedures.

This method is commonly used in small-batch production or mixed model lines. It’s less capital-intensive than in-mold systems but requires quality oversight to maintain alignment and glue distribution.

| Pros | Cons |

| Flexible glue selection | Lower alignment accuracy than in-mold |

| Easier maintenance | Longer cycle time |

| Lower tooling cost | Potential glue inconsistency |

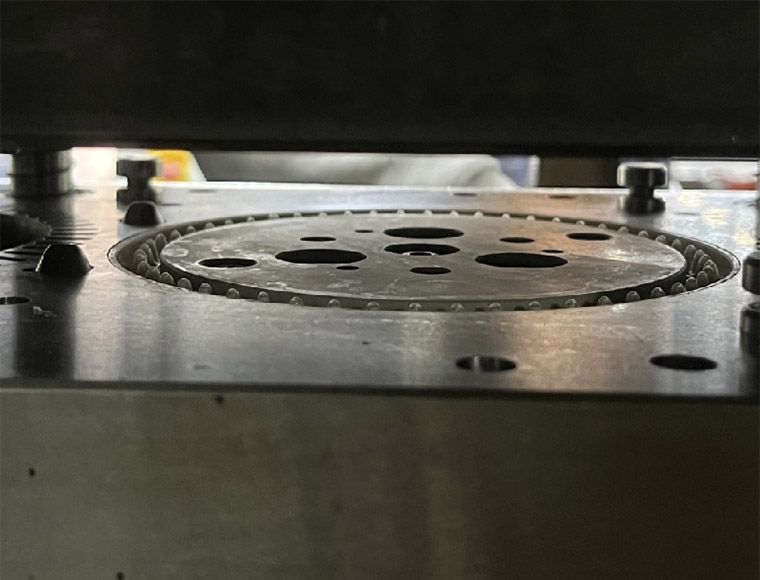

Progressive Mold Self-Interlocking Stacking

Progressive mold self-interlocking stacking locks laminations together through a progressive die, eliminating the need for adhesives or fasteners.

This approach excels in high-volume production with standardized parts. Built-in interlocking features ensure mechanical stability without extra materials, reducing cycle time and labor costs.

| Pros | Cons |

| Very fast throughput | Interlocking design limits geometry |

| No adhesives needed | High precision tooling required |

| Reliable stack quality | Expensive die development |

Compound Mold Single Punch Self-interlocking Stacking

With compound mold single punch self-interlocking stamping, forming, and stacking occur simultaneously using a compound mold and single punch stroke. This method minimizes handling steps and maximizes efficiency.

Ideal for ultra-high volume motor cores, the result is one of the fastest stacking processes available, though tooling complexity is substantial.

| Pros | Cons |

| Extremely high production efficiency | Very high tooling cost |

| Minimal handling errors | Limited design flexibility |

| High stack consistency | Long lead time to develop molds |

Rivet Stacking

Rivet Stacking involves aligning laminations with pre-punched holes and inserting rivets that are deformed to clamp the stack. It is a traditional mechanical fastening method.

Though less popular in high-efficiency designs, rivet stacking still finds use in conventional industrial motors where rugged construction outweighs peak performance needs.

| Pros | Cons |

| Simple and reliable | Adds weight to core |

| Low upfront tooling cost | Can increase core loss |

| Good mechanical strength | Potential for vibration and noise |

Welding Stacking

Welding Stacking joins laminations through techniques like resistance welding or laser welding. Without the need of additional adhesives or mechanical fasteners, weld spots fuse laminations into a cohesive core.

Welded stacks are common in high-speed and high-stress applications such as heavy industrial drives. In particular, laser welding provides accurate heat management that lessens magnetic deterioration and distortion.

| Pros | Cons |

| Strong mechanical bond | Heat can deform laminations |

| No additional components | Welding equipment is costly |

| Good for high-stress operation | Precision process control needed |

Self-Adhesive Stacking

Self-Adhesive Stacking uses pre-coated laminations with adhesive that activates under heat or pressure. This removes the need for separate glue dispensing systems and simplifies stacking.

Used frequently in compact and consumer motor designs, self-adhesive stacking reduces assembly complexity. It is suitable for moderate performance motors where reduced assembly steps and cleanliness are priorities.

| Pros | Cons |

| Clean and simplified process | Adhesive limits high-temp use |

| Uniform bonding | Adhesive aging risk |

| Lower equipment cost | Lower mechanical strength than welding |

Bolt Stacking

Bolt stacking secures laminations together with bolts and nuts through aligned holes. This method allows stacks to be disassembled—useful in prototypes and test environments.

Bolt stacking offers flexibility and serviceability but is rarely used in mass production due to labor intensity and lower magnetic performance relative to bonded or welded stacks.

| Pros | Cons |

| Easy to assemble and disassemble | Adds weight and size |

| Adjustable stack length | Time-intensive assembly |

| Ideal for R&D | Poor magnetic characteristics |

Buckle or Clamping Stacking

Buckle or Clamping Stacking uses external clamps or bands to hold laminations together without glue, welding, or permanent fasteners. This method is often seen in testing, temporary assembly, or lab environments.

Clamping methods offer quick assembly and disassembly, but they lack the long-term mechanical reliability needed for production motors that operate at high speeds or temperatures.

| Pros | Cons |

| Fast and reversible assembly | Uneven pressure can occur |

| No permanent bonding required | Clamps increase size and cost |

| Reusable fixtures | Limited long-term stability |

Al-Casting or Cu-Casting Stacking

Melted copper or aluminum is poured around the lamination stack in Al-casting or Cu-casting stacking. This method not only fixes the laminations but also integrates rotor bars and end rings simultaneously in many induction motors.

Casting methods are intrinsic to rotor manufacturing in many AC induction motors, offering superior conductivity and mechanical integrity. The trade-off is the need for thermal control and specialized casting equipment.

| Pros | Cons |

| Extremely strong mechanical bond | High thermal stress on laminations |

| Excellent electrical performance (Cu) | Complex and expensive equipment |

| Integrated manufacturing step | Potential distortion with heat |

Choosing the Right Method

Selecting the ideal stacking method hinges on several factors:

Performance & Efficiency

- Low core loss priority: In-Mold Glue, Progressive Self-Interlocking, Self-Adhesive

- Structural strength priority: Welding, Casting

- Balanced performance: Out-Mold Glue, Compound Mold Single Punch

Production Volume

- High volume: Progressive Mold, Compound Mold Single Punch

- Medium volume: In/Out-Mold Glue, Self-Adhesive

- Low volume / R&D: Bolt, Clamping

Cost & Tooling

- Low tooling cost: Rivet, Bolt, Clamping

- Moderate: Out-Mold Glue, Self-Adhesive

- High tooling cost: In-Mold Glue, Progressive & Compound Mold, Casting

Design Flexibility

- High flexibility: Out-Mold Glue, Bolt, Clamping

- Moderate: Self-Adhesive

- Limited flexibility: Self-Interlocking and Casting